Mapped Parcels as a Social Graph: Rethinking Boundaries through Relationships

/In the digital age, we're increasingly accustomed to understanding complex systems through networks—think of social media, where relationships define the structure of our online lives. Surprisingly, a similar networked logic underpins a domain you might not associate with your LinkedIn profile: cadastral mapping. When we map parcels—individual units of land—we're not just drawing boundaries; we're mapping relationships. The parcel map behaves much like a social graph, where the connections between features are just as meaningful as the features themselves.

The Parcel Network: More Than Lines on a Map

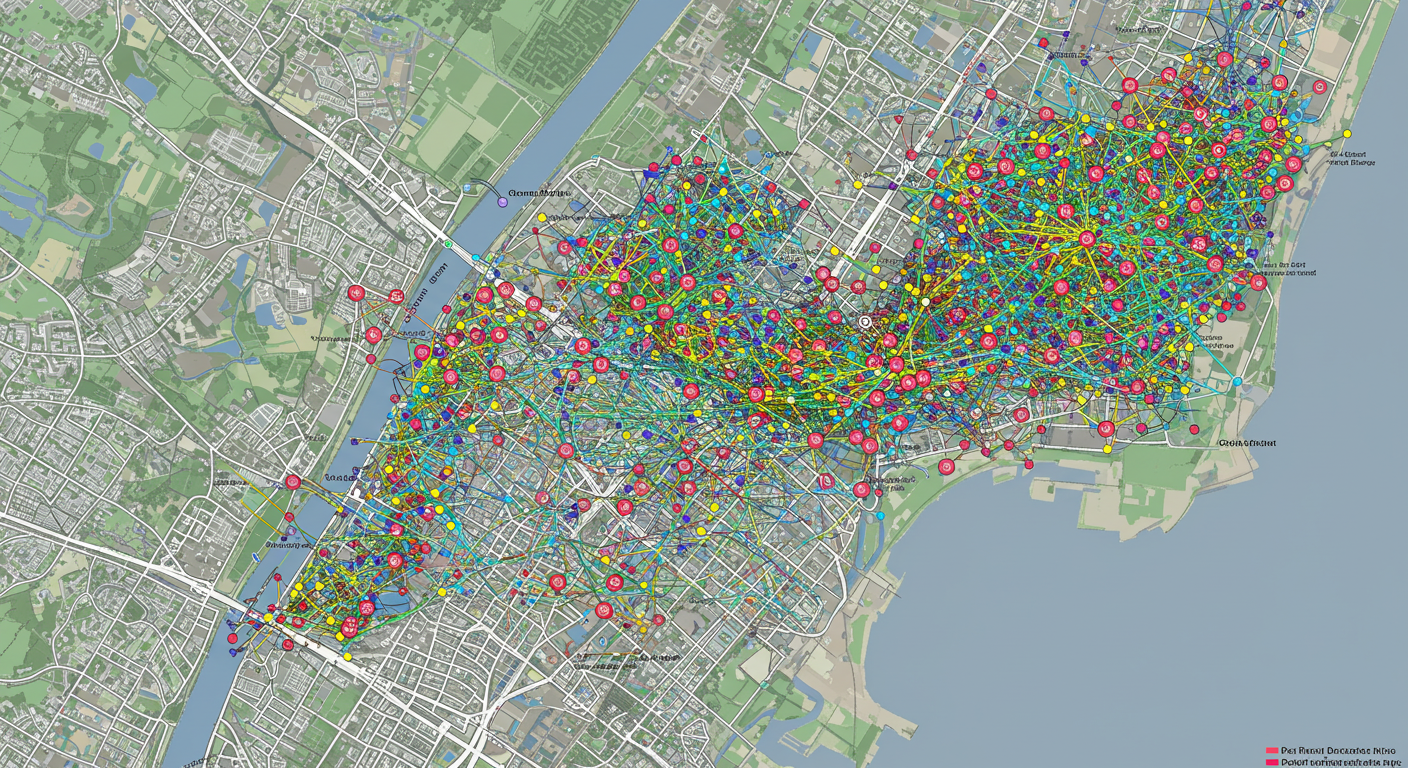

Parcel BOUNDARIES as a social network

Traditionally, cadastral mapping involved defining a piece of land using physical monuments—iron pipes, fence posts, trees, or stones—identified in a written legal description. These monuments, when connected in sequence, form the boundary of the parcel. But those connections do more than define shape—they represent dependencies and relationships between real-world reference points. In essence, each monument is a "node" and each boundary segment a "link" between them.

This begins to look a lot like a social graph, where people (nodes) are connected by relationships (edges). In social media, these edges represent friendships or interactions. In parcel mapping, the edges represent bearing and distance relationships, forming the legal skeleton of property rights.

From Monument to Monument: Relationship-Driven Mapping

Legal descriptions often refer to a starting point—"Beginning at a point marked by an iron rod..."—and proceed from one known feature to the next. These features, or described monuments, act like mutual friends connecting two people in a social graph. The location of one monument may only be understood in reference to another, just like knowing one person through mutual acquaintances.

This relational dependency is critical. If one monument is disturbed or missing, the integrity of the entire network can be affected, much like how the removal of a key hub in a social graph can isolate or distort entire clusters of relationships.

Parcel Fabric: Modeling the Graph

Modern GIS platforms like ArcGIS Pro’s Parcel Fabric are explicitly built to manage these relationships. Rather than treating parcels as isolated polygons, the Parcel Fabric treats them as interconnected networks, where points (monuments), lines (boundaries), and polygons (parcels) all maintain topological and legal relationships with each other.

Each parcel is "friends with" its adjacent parcels via shared boundaries. These shared edges have identities and rules, and changes on one side must be reflected on the other. Just as in a social graph, where two connected users might share data or influence, two neighboring parcels may share responsibility for a fence, easement, or setback line. Their boundaries are co-defined, and edits to one must propagate through the network to maintain consistency.

Why This Matters

Thinking of parcels as a social graph helps us understand:

Interconnectedness:

A parcel is never isolated; its identity is formed through its relationships.

Dependency:

Legal and spatial accuracy depends on a web of references, not just coordinates.

Change management:

Altering one part of the graph (e.g., a boundary adjustment) requires network-aware updates to preserve overall coherence.

Data modeling:

Modern GIS must support not just geometry, but relational logic—like how Facebook doesn’t just store user profiles, but how those users are connected.

A Human-Scale Network

At its core, parcel mapping is about how humans claim, define, and relate to land—and to each other. Each point and line on a cadastral map has a story: a handshake across a fence, a court battle over a tree line, a surveyor’s trek through the woods to pound in a corner monument. These aren't just measurements; they’re relationships. And in treating a parcel map as a social graph, we reveal the deeply human network embedded in our landscape.

Final Thought:

Next time you look at a parcel map, don’t just see shapes—see a web of relationships, a living social graph made of monuments, boundaries, and shared histories.