From Words to Dirt: How Legal Descriptions Become Physical Reality

/Land ownership begins not with fences or roads, but with words.

A parcel’s legal description—whether a metes-and-bounds call written in flowing 19th-century prose or a terse reference to a recorded plat—exists first as an abstract construct. It is a linguistic attempt to define something that must ultimately exist on the ground. The journey from those words on paper to steel pins, stone corners, and occupied land is where law, measurement, and professional judgment converge. This translation from text to terrain is one of the most fundamental—and misunderstood—processes in land administration.

Legal Descriptions as Abstract Systems

At their core, legal descriptions are systems of reference. They do not describe land as it appears, but as it is legally intended to exist. Bearings, distances, curve data, aliquot parts, and references to adjoining ownership form a relational framework rather than a geometric one. Even modern coordinate-based descriptions rely on assumptions about datums, projections, and the permanence of reference systems.

Older descriptions often amplify this abstraction. Early surveyors wrote descriptions using natural landmarks, locally understood monuments, and customary units of measure. Phrases like “to a large oak,” “along the meander of the creek,” or “thence with the lands of Smith” were not imprecise at the time—they were practical. The land itself was the map, and the words merely pointed the reader toward a shared physical understanding.

Monuments: The Legal Bridge Between Text and Ground

When a legal description meets the earth, monuments become paramount. In boundary law, monuments—whether natural or artificial—generally control over measurements. A stone set in 1840, a blazed tree noted in a deed, or an iron rod placed during an original subdivision survey often carries more legal weight than a modern GPS observation.

This hierarchy reflects a core legal principle: the intent of the original grant controls. Monuments are considered the physical manifestation of that intent. Even if a distance is short or long, or a bearing does not mathematically close, the monument anchors the description in reality. The ground, as originally marked, becomes the ultimate reference.

This is why surveyors often say they “follow the footsteps” of the original surveyor. Their task is not to create a better boundary, but to locate the boundary that already exists in law.

Measurements as Evidence, Not Authority

Modern technology has transformed how accurately we can measure distance and direction. Total stations, GNSS, and parcel fabrics allow us to detect discrepancies measured in hundredths of a foot. Yet greater precision does not equate to greater authority.

Measurements serve as evidence in boundary retracement, not as the final arbiter. A call for 100 feet that measures 98.7 feet today does not, by itself, move a boundary. The discrepancy may reflect original equipment limitations, terrain constraints, magnetic declination shifts, or simple transcription errors. The surveyor’s role is to weigh measurements against monuments, record evidence, occupation, and senior rights.

In this sense, boundary determination is closer to historical analysis than engineering. The best solution is not always the mathematically perfect one, but the one most faithful to the original intent and long-standing reliance.

Professional Judgment in the Field

No legal description can anticipate every condition encountered on the ground. Monuments may be lost, moved, or destroyed. Natural features may shift or disappear. Adjacent descriptions may conflict. At these moments, professional judgment becomes the critical tool.

Surveyors and cadastral professionals synthesize deed research, field evidence, legal precedent, and spatial relationships to resolve ambiguity. This judgment is not arbitrary; case law, professional standards, and ethical obligations bound it. Yet it remains inherently interpretive.

Two professionals may reasonably reach different conclusions from the same evidence, which is why boundary disputes so often end up in court—and why courts frequently defer to well-documented professional opinions.

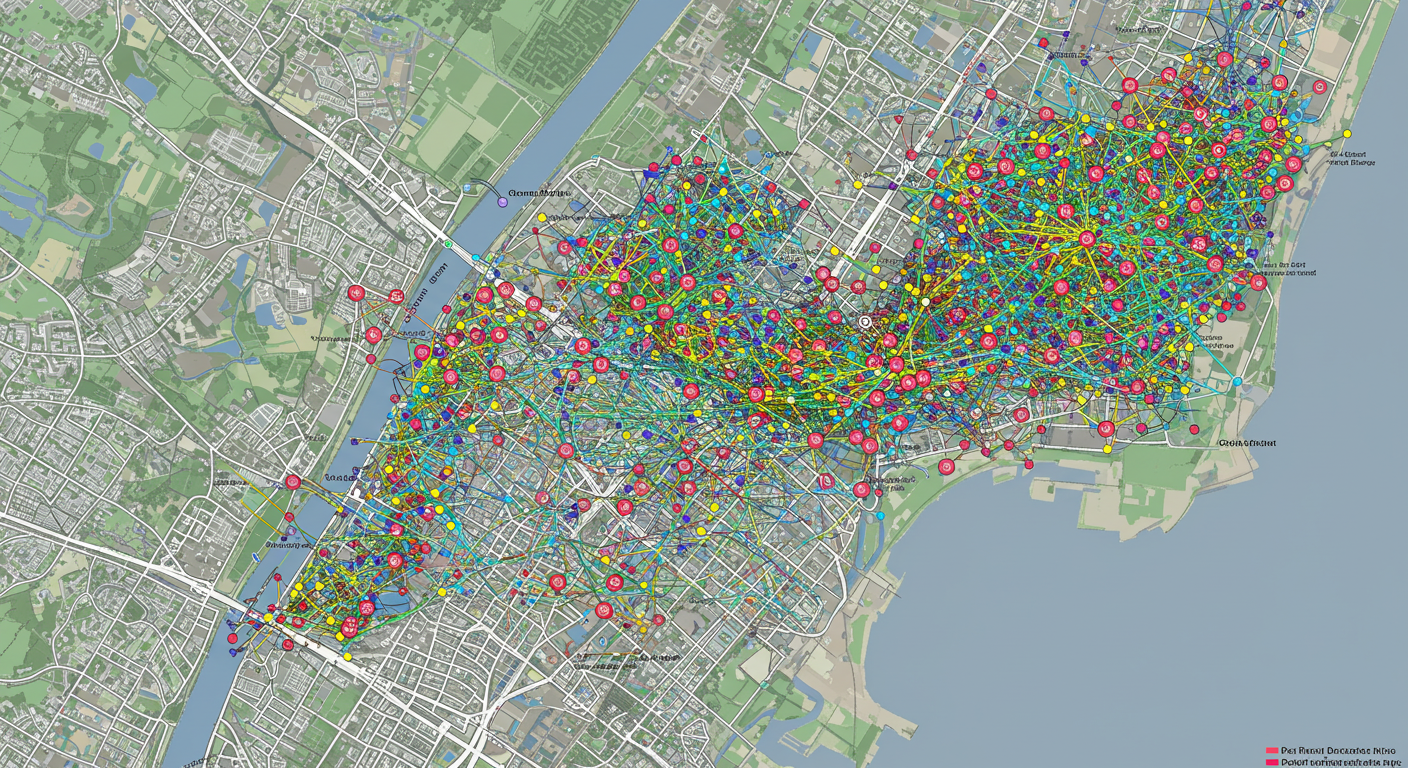

GIS, Parcel Mapping, and the Illusion of Certainty

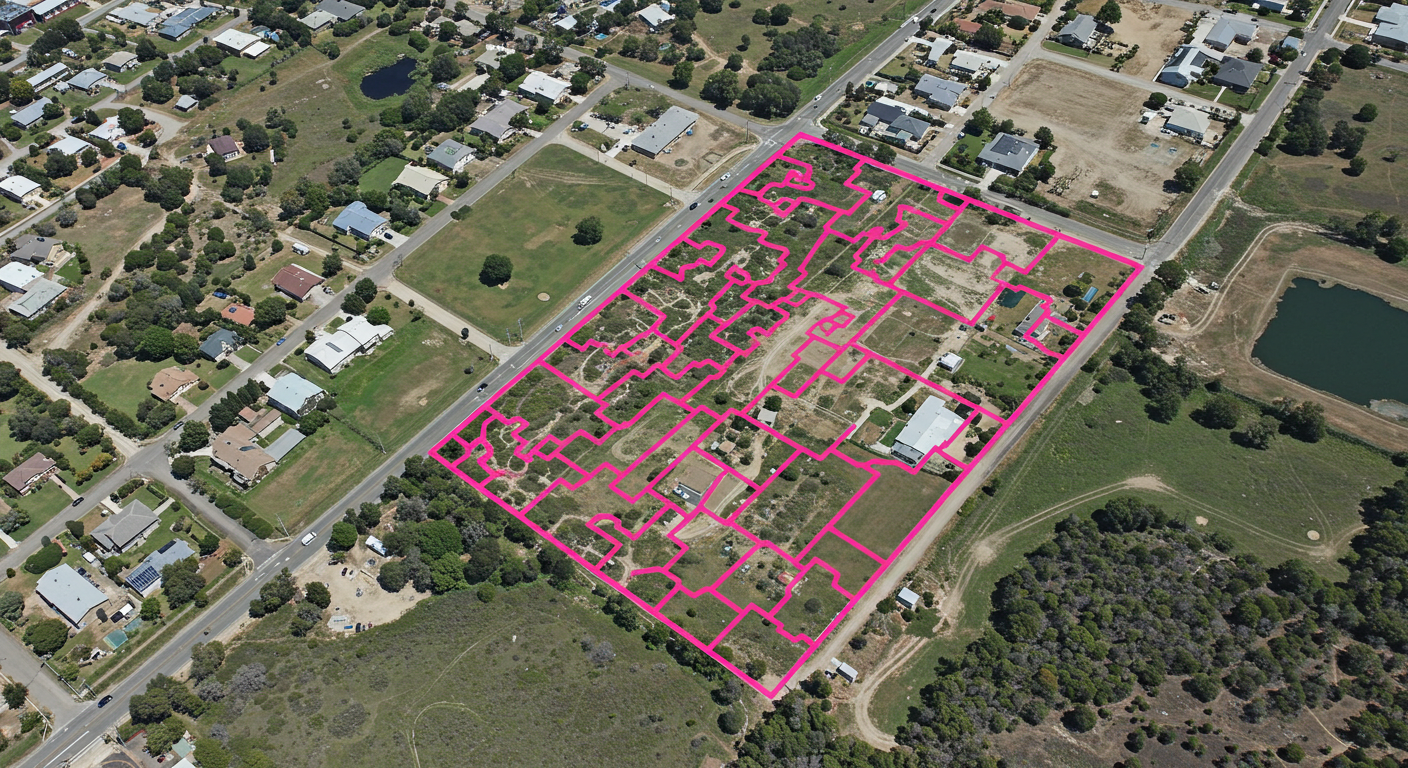

In GIS and cadastral mapping, legal descriptions are often reduced to lines, polygons, and coordinates. While this abstraction is necessary for analysis and administration, it can obscure the conditional nature of boundaries. A parcel polygon may appear definitive on a screen, but it is only as authoritative as the legal and physical evidence behind it.

Parcel mappers must reconcile survey-level nuance with system-wide consistency. This requires clear lineage, confidence modeling, and acknowledgment that not all parcel boundaries carry equal evidentiary weight. The map is a representation, not the boundary itself.

From Description to Occupation

Ultimately, the transformation from words to dirt is validated by occupation and reliance. Fences are built, buildings are constructed, taxes are assessed, and land is conveyed based on interpreted boundaries. Over time, these physical manifestations can reinforce or even override written descriptions through doctrines like acquiescence, prescription, and estoppel.

What began as ink on paper becomes a lived reality.

Conclusion: Respecting the Translation

Understanding how legal descriptions become physical reality requires respecting both sides of the translation. The words matter, but so does the dirt. Monuments matter, but so does context. Precision matters, but so does intent.

For surveyors, GIS professionals, planners, and land administrators, this process is a reminder that land is not purely geometric. It is legal, historical, and human. Every boundary tells a story—not just of where a line lies, but of how generations have agreed, argued, and ultimately lived with that line on the ground.

From words to dirt, the boundary endures.