Least Squares Adjustments in GIS: Powerful Mathematics, Conditional Truth

/Least Squares Adjustments in GIS: Powerful Mathematics, Conditional Truth

Least squares adjustment is one of the most important mathematical tools in surveying, geodesy, and spatial data science. It is elegant, statistically rigorous, and foundational to the construction of modern coordinate systems, GPS observations, and control networks. Yet within GIS workflows, least squares adjustment is often misunderstood, misapplied, or assumed to be a universal solution for “making data better.”

This misunderstanding is not a failure of the mathematics—it is a failure to respect the assumptions under which least squares produces meaningful results. GIS data lives at the intersection of measurement, interpretation, and representation. Least squares can be transformative when applied to the right kind of data, and actively misleading when applied to the wrong kind.

Understanding when least squares adjustment is appropriate in GIS—and when it is not—is essential for anyone responsible for spatial accuracy, legal defensibility, or analytical integrity.

What Is a Least Squares Adjustment?

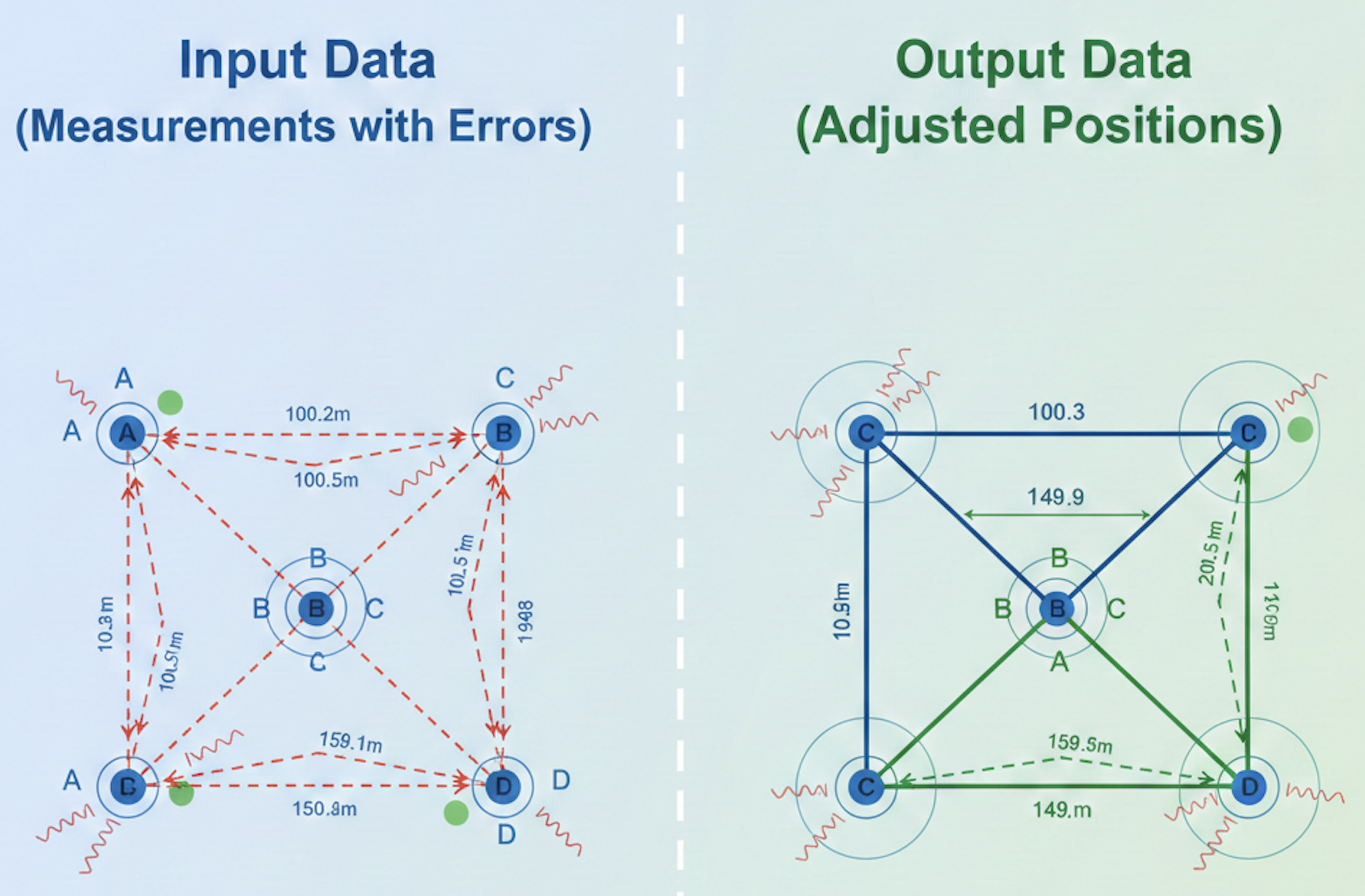

At its core, a least squares adjustment is a statistical method for estimating unknown values by minimizing the sum of the squared residuals between observed and computed values. In plain terms, it finds the “best-fit” solution when observations contain unavoidable error.

In surveying, this typically means:

Multiple measurements of distances, angles, or vectors

Redundant observations of the same unknown

Known statistical properties of measurement error

Rather than forcing observations to agree perfectly (which they never do), least squares distributes the error across the network in a mathematically optimal way, producing:

Adjusted coordinates

Residuals for each observation

Measures of uncertainty (variance, standard deviation)

Statistical indicators of reliability

This approach is not about perfection—it is about probability.

The Assumptions Behind Least Squares

Least squares adjustment only produces meaningful results when its core assumptions are met:

Observations are measurements, not interpretations

The input data must be derived from physical measurements, not inferred or digitized.

Errors are random, not systematic

Least squares assumes that errors are normally distributed and unbiased. It cannot correct consistent directional errors.

Observations have known or estimable precision

Measurements must be weighted appropriately. A GPS baseline and a digitized line from a scanned map are not equivalent observations.

Redundancy exists

There must be more observations than unknowns. Without redundancy, there is nothing to adjust.

The model reflects physical reality

The geometry being adjusted must correspond to how the data was actually collected.

When these assumptions hold, least squares is extraordinarily powerful. When they do not, the math still produces an answer—but that answer may be meaningless.

When Least Squares Adjustment Is Applicable in GIS

Control Networks and Survey-Grade Data

Least squares is entirely appropriate—and often essential—when GIS data is derived from:

GNSS observations

Total station measurements

Control point networks

Geodetic surveys

In these cases, GIS is acting as a container for survey-grade data, not a replacement for survey methodology. Parcel fabric control points, monument coordinates, and reference stations benefit directly from least squares adjustment because they originate from measurement processes with known precision.

Here, GIS becomes a spatial database for statistically defensible coordinates.

Parcel Fabric Adjustments Based on Measurements

Within parcel fabric systems, least squares adjustment can be appropriate when:

Parcels are built from bearings and distances

Measurements are redundant and connected

Control points constrain the solution

The adjustment respects the hierarchy of evidence (monuments over dimensions)

Used correctly, least squares helps reconcile small discrepancies while honoring original survey intent. It does not “fix” bad data; it distributes uncertainty while preserving relationships.

This is especially valuable when integrating multiple surveys of differing quality over time.

Network Conflation with Known Error Models

In limited cases, least squares can be applied to GIS conflation workflows when:

Source datasets have known accuracy characteristics

Positional uncertainty is explicitly modeled

The adjustment is constrained by reliable control

For example, aligning utility networks or transportation features derived from survey data may benefit from constrained least squares methods.

The key is that the adjustment is informed by measurement theory—not just geometry.

When Least Squares Adjustment Is Not Applicable in GIS

Digitized or Interpreted Features

Least squares should not be applied to:

Digitized parcels from scanned maps

Heads-up digitizing of historical plats

Features derived from aerial imagery without ground control

These are interpretations, not measurements. Any apparent precision is artificial. Applying least squares in this context gives the illusion of statistical rigor without any factual basis for error modeling.

The math is correct; the premise is false.

Legal Boundaries Defined by Monuments

Property boundaries are not statistical constructs. They are legal facts defined by:

Original monuments

Surveyor intent

Case law and doctrine

Least squares minimizes error; boundary law prioritizes evidence. These are fundamentally different objectives.

Using least squares to “smooth” or “improve” boundary geometry risks violating the legal hierarchy of evidence, particularly when:

Monuments disagree with the record dimensions

(This is a BIG one because parcel boundaries are defined by monuments, not measurements)

Occupation conflicts with measured geometry

In these cases, judgment—not mathematics—controls the outcome.

Systematic Errors and Biases

Least squares cannot fix:

Incorrect coordinate system definitions

Projection distortions are applied inconsistently

Datum mismatches

Bad control points

If errors are systematic, least squares will simply distribute the bias across the dataset, making the results look better while embedding the problem more deeply.

This is especially dangerous in enterprise GIS environments, where adjusted data propagates downstream into analysis, taxation, and public consumption.

“Making Data Look Better”

Perhaps the most common misuse of least squares in GIS is aesthetic correction:

Making lines meet

Removing gaps or overlaps

Aligning datasets visually

These are cartographic problems, not statistical ones. Least squares is not a tool for visual cleanup. When used this way, it replaces data integrity with mathematical cosmetics.

While based on Measurement, GIS Is Not a Measurement System

A critical distinction must be made: GIS is primarily a representation and analysis system, not a measurement system.

Surveying produces observations.

GIS stores, visualizes, and analyzes the results.

Least squares belongs to the observation phase. When it is pulled downstream into GIS without regard for its origin, it becomes disconnected from reality.

This is why least squares feels both powerful and dangerous in GIS environments—it operates with authority, even when its assumptions have been violated.

The Role of Professional Judgment

No algorithm can determine whether least squares is appropriate for a dataset. That decision requires:

Understanding how the data was created

Knowing what the data is legally or analytically used for

Recognizing the difference between accuracy, precision, and truth

In cadastral GIS, especially, least squares must serve as evidence—not replace it.

Conclusion: Respect the Tool, Respect the Context

Least squares adjustment is one of the great achievements of applied mathematics. In the right context, it enables modern surveying, global positioning, and high-precision spatial infrastructure.

In GIS, however, it must be applied with restraint and humility.

Used appropriately, least squares clarifies uncertainty and strengthens spatial integrity. Used indiscriminately, it creates false confidence and obscures the very realities GIS is meant to represent.

The question is not whether least squares works—it always does.

The question is whether it works for the truth you are trying to model.